Liminal Edge: The Former Boca Juniors Sports City

By Mutar Estudio for El Barro, a curatorial project by Monoambiente, an experimental consortium in architecture and design, based on the collective research of a unique territory: the lands the city reclaimed from the Río de la Plata.

"As if ruin were nature’s revenge upon culture, reshaping it in its own image; or as if our architecture and our cities were nothing more than an act of will to which stone and water submit, only to then violently shake off that yoke and return to the dominion of nature."

— Georg Simmel

As the hypothesis of the Anthropocene advances, it becomes essential to intertwine the histories of power with those of environmental transformation. The coastline of Buenos Aires is a key stage where the interplay of social forces is materially inscribed, becoming a sign of its time. The former Boca Juniors Sports City, as a fragment of this edge, is a clear example of how socioeconomic frameworks and political will leave their mark on the landscape.

This history of the privatization of public land/water begins in the mid-20th century, sustained by the faith and sense of belonging of a football club. The first landfills were dumped by Boca’s truck drivers who believed in the dream of a leader—Alberto J. Armando—who promised transcendence. That popular will to build a second stadium on the water was inscribed in a national developmentalist context, under President Arturo Illia, who granted the land in exchange for the construction of public recreational and sports facilities.

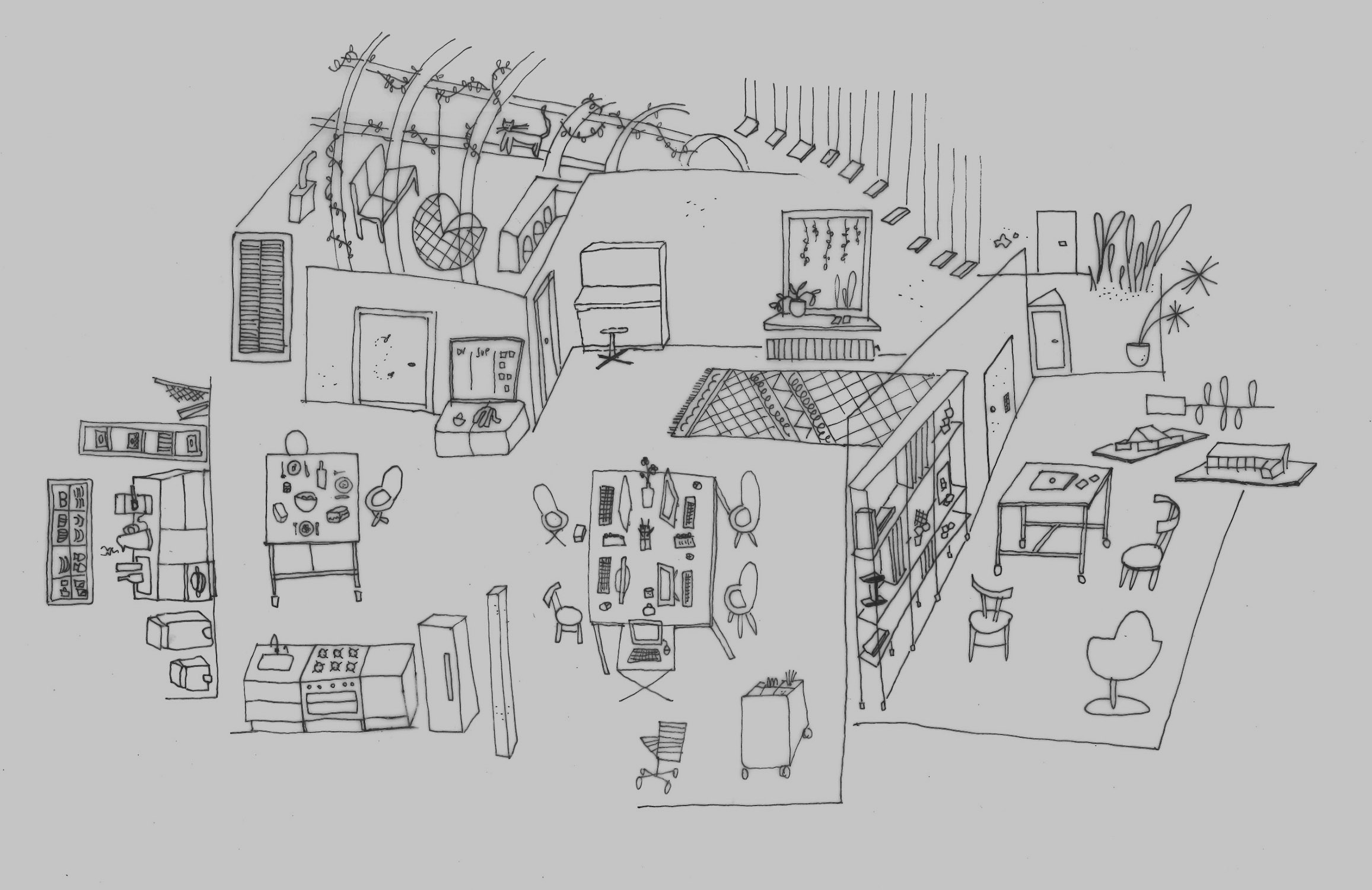

The country’s persistent structural crises and the club’s lack of financial resources prevented the works from being completed, leaving the project stalled in a sequence of interruptions, displacements, and reconfigurations. The image of splendor froze into a nostalgic postcard, and the wetland fell silent. Over time, the river itself deposited sediments between the projected islands, doubling the site’s surface area in a topographic metamorphosis of natural temporality. The infrastructures that once hosted leisure and spectacle—abandoned and left without maintenance—dissolved in the open air, forming an architectural bestiary, a catalog of iconic creatures of decay.

Today’s landscape is a liminal space, both for its transitory condition—something always about to change—and for the dreamlike scene created by the strangeness of its occupation. The ruins of this interrupted fantasy, overtaken by spontaneous wild vegetation, coexist with containers, helicopters, fishermen, and private surveillance devices. This borderland awaited new conditions for reinterpretation. It was made an exception within the new urban code, which authorized the construction of residential towers and exclusive services in exchange for a percentage of public parkland facing a neighborhood undergoing reurbanization.

Between the criollo Venice imagined by a popular club and the corporate Dubai projected by real estate capital, lie decades of transition that express the convergence and dispute between human will and the power of nature. Its imprint today bears witness to the memory of fractured progress.

Formed by Lucila Ottolenghi, Natalia Kahanoff, Luciana Casoy y Florencia Lopez Iriquin in the City of Buenos Aires. His main interest lies in the realization of projects and materialization of single-family and collective housing, both in transformations of pre-existing and in new construction. His professional practice also addresses the field of teaching and both theoretical and practical research. It is a space for work and friendship that combines diverse but defined roles. Each project is taken as a field of inquiry to experiment with approach methods that allow heterogeneous results at all scales.

Website: Pinkus